When Work Isn't Enough: What Census Data Reveals About Silicon Valley's Working Poor

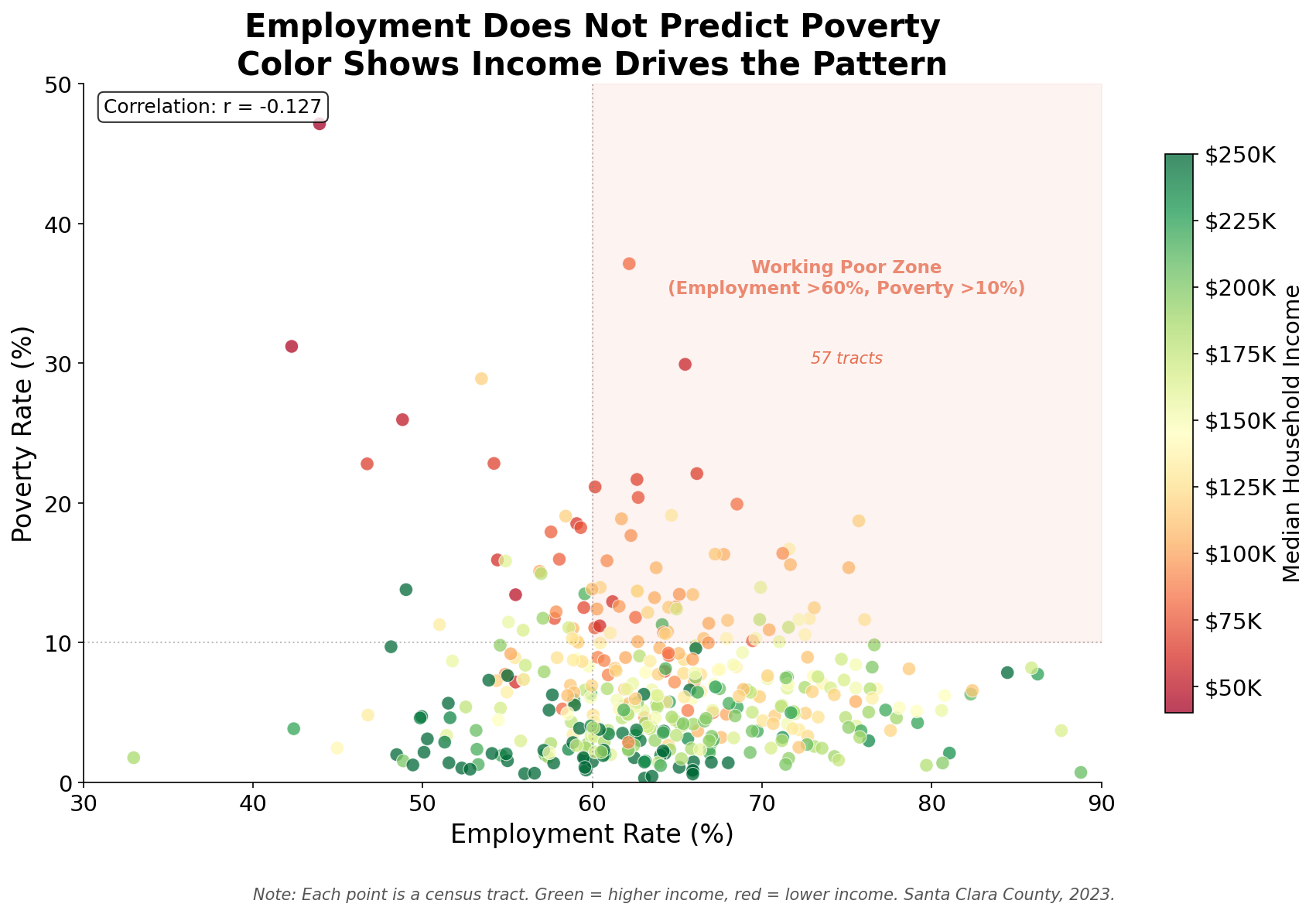

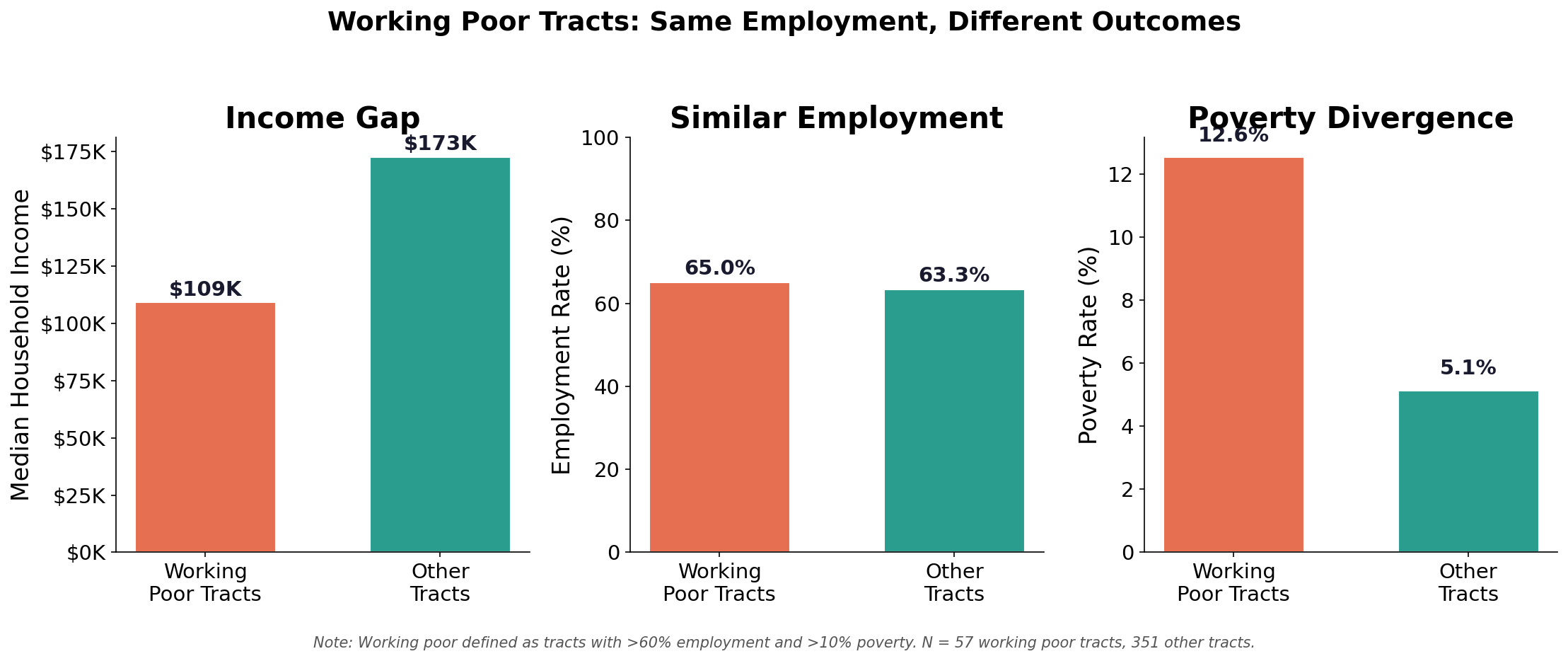

In 57 census tracts across Santa Clara County, more than 60% of working-age adults are employed. These same tracts have poverty rates above 10%.

This pattern, high employment alongside meaningful poverty, appears in neighborhoods home to 256,773 people. The correlation between employment rate and poverty rate across all 408 county tracts? r = -0.063, essentially zero.

Since employment doesn't predict poverty in Silicon Valley, we should think about what Census wage and income data can show us.

The National Narrative vs. Local Reality

The standard story: Poverty results from unemployment. Get people jobs, reduce poverty.

The evidence suggests otherwise in high-cost regions. Research on labor market polarization shows wage growth concentrated at the top and bottom, hollowing out the middle (Autor & Dorn, 2013). Studies of geographic variation in economic mobility reveal that some regions break the employment-poverty link entirely (Chetty et al., 2014).

What we find in Santa Clara County:

- Employment rates remain high even in highest-poverty tracts (62.7% vs 65.8%)

- Only 3.1 percentage point difference across poverty quintiles

- The scatter plot below demonstrates the near-zero relationship

Why this matters: If we assume poverty equals joblessness, we misdiagnose the problem and misallocate resources.

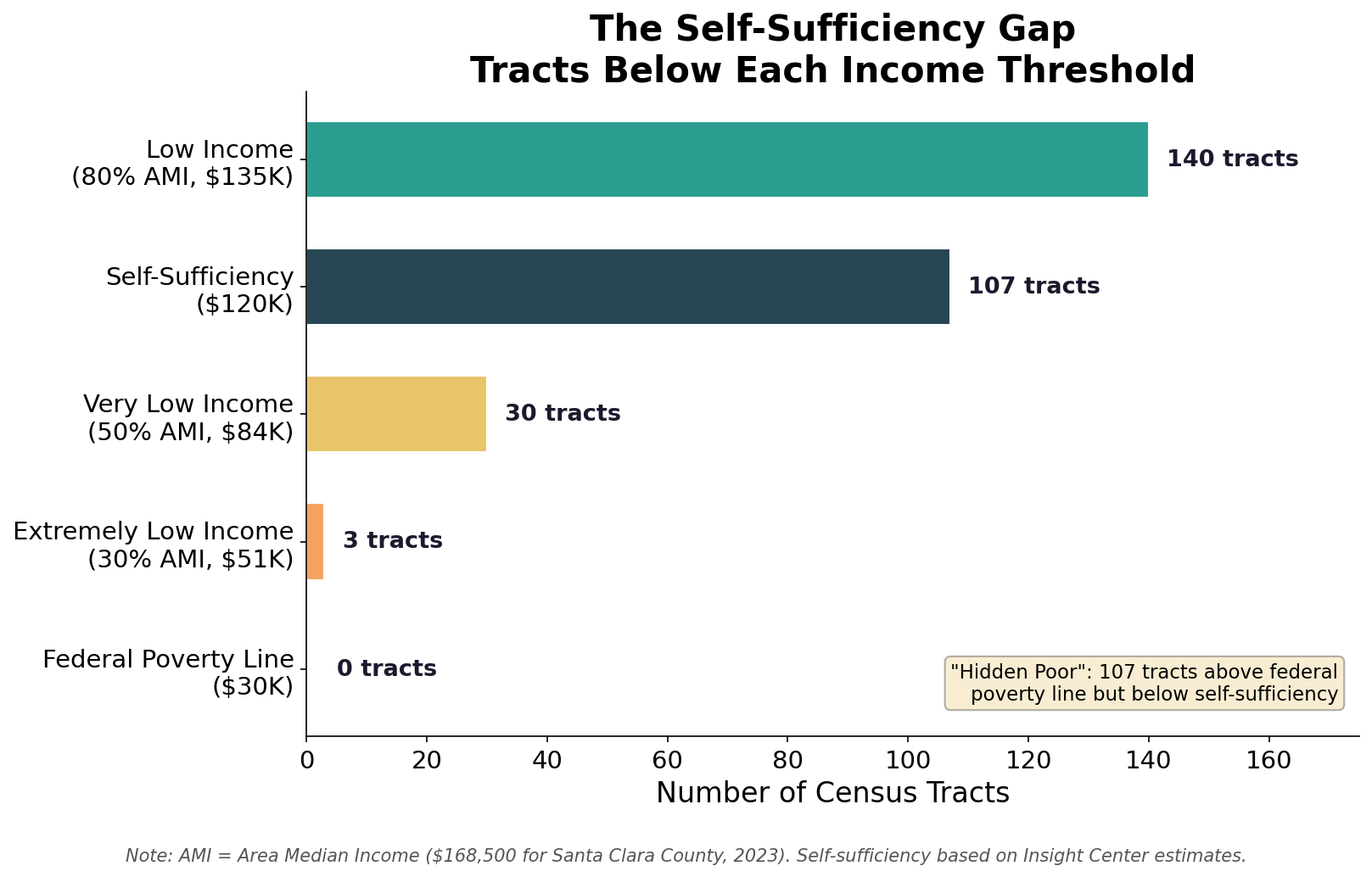

The Self-Sufficiency Gap

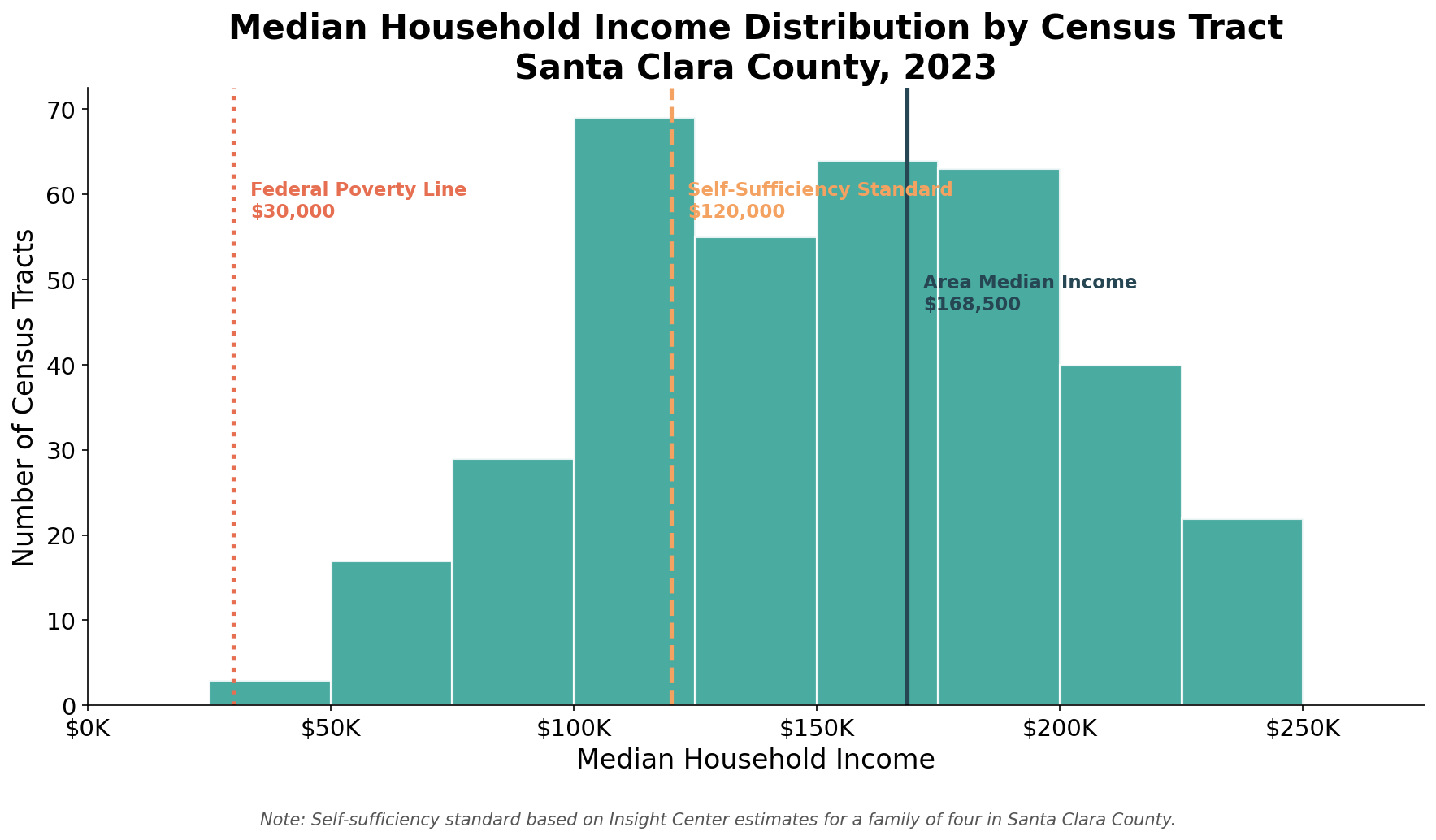

The federal poverty line ($30,000 for a family of four in 2023) was designed in the 1960s based on food costs (Fisher, 1992). It assumes food is one-third of a family's budget, an assumption that no longer holds, especially in high-cost regions.

What "self-sufficiency" actually requires:

- Santa Clara County self-sufficiency for a family of four: ~$120,000/year (Insight Center for Community Economic Development)

- HUD Area Median Income 2023: $168,500

- Federal poverty line: $30,000

The "hidden poor": 107 tracts fall below the self-sufficiency threshold but would never be identified by federal poverty measures. This represents 464,086 people.

Defining "Working Poor" Tracts

We flag tracts as "working poor" when employment rate exceeds 60% (people are working) and poverty rate exceeds 10% (but meaningful poverty persists). This is a tract-level proxy; individual-level "working poor" data would require different methodology (Newman, 1999).

What we find:

- 57 tracts (14% of county) meet both criteria

- 256,773 residents live in these tracts

The employment rates are nearly identical: 65% in working poor tracts vs 63% in other tracts. The difference is income: $109,000 median in working poor tracts vs $173,000 elsewhere.

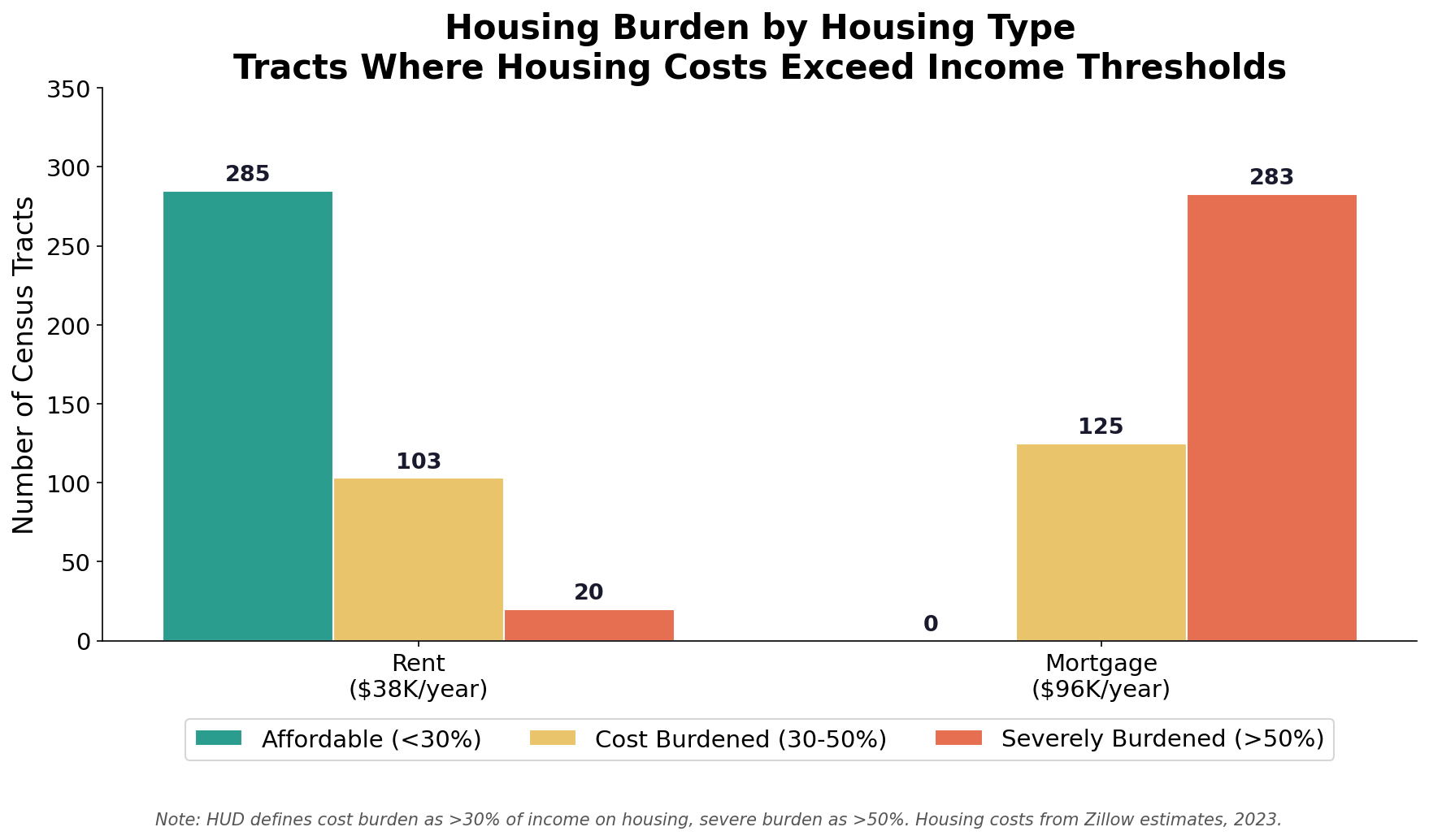

The Housing Equation

Housing costs vary dramatically by region. The same $80,000 income provides different standards of living in different metros (Moretti, 2012).

Using median rent ($38,400/year) and median mortgage (~$96,000/year from Zillow estimates), we calculated housing burden for each tract:

At the county's median income of $162,321:

- Rent consumes 24% of income (manageable)

- Mortgage consumes 59% of income (severely burdened)

This explains why employment doesn't lift people out of poverty here: wages have not kept pace with housing costs (Joint Center for Housing Studies, 2024).

The Scale of the Gap

For the 107 tracts below the self-sufficiency threshold:

- Average gap: $23,431 per household below what's needed

- Maximum gap: $79,833 (lowest-income tract)

- Aggregate gap: ~$9.9 billion

This is a rough estimate of the "shortfall" between what households in below-self-sufficiency tracts earn and what they would need to meet basic expenses without assistance. It contextualizes why food insecurity, housing instability, and other hardships persist despite low unemployment.

What the Data Can and Can't Tell Us

What the data show:

- Tract-level correlation between employment and poverty is near zero

- Many tracts have high employment and meaningful poverty simultaneously

- Income thresholds reveal a large population above federal poverty but below self-sufficiency

What the data don't show:

- Individual-level working poor (we have tract aggregates, not household data)

- Causation (why wages are low: could be occupation mix, hours worked, multiple jobs)

- Dynamics (people may cycle in and out of poverty; this is a snapshot)

Final Thoughts

The 1996 welfare reform enshrined a "work first" philosophy: the assumption that employment is the primary path out of poverty (Blank, 2002; Haskins, 2006). This view shaped policy for decades, with 43 states by 2000 requiring welfare recipients to engage in work activities immediately or shortly after receiving benefits. Yet research on these policies found that "the incomes of women who left welfare rose little because the loss of benefits almost cancelled out the increase in earnings" (Blank, 2002). In Santa Clara County, our data suggest a similar story plays out at the neighborhood level.

When we examine 408 census tracts, we find employment rates that barely vary by poverty level. We find 107 tracts (home to nearly half a million people) where median incomes fall below what families need to be self-sufficient. We find housing costs that consume impossible shares of income even for employed households.

The working poor aren't failing to work. They're working in an economy where wages haven't kept pace with costs.

Understanding this through data helps us ask better questions: not "why won't they work?" but "why doesn't work pay enough?" The publicly available Census data we've examined here can't answer that question, but it can show us the question we should be asking.

Methodology Note

Data Sources: U.S. Census Bureau ACS 5-Year Estimates (2019-2023): B19013 (Median Household Income), B19001 (Income Distribution), B17001 (Poverty Status), C17002 (Ratio of Income to Poverty), B23025 (Employment Status). Self-Sufficiency Standard from Insight Center for Community Economic Development. HUD Area Median Income 2023.

Sample: 408 census tracts, Santa Clara County, California

Working Poor Definition: Tracts with employment rate > 60% and poverty rate > 10%

Housing Burden Estimates: Based on Zillow median rent and mortgage estimates for Santa Clara County, 2023

References

Autor, D. H., & Dorn, D. (2013). The growth of low-skill service jobs and the polarization of the US labor market. American Economic Review, 103(5), 1553-1597.

Blank, R. M. (2002). Evaluating welfare reform in the United States. Journal of Economic Literature, 40(4), 1105-1166.

Chetty, R., Hendren, N., Kline, P., & Saez, E. (2014). Where is the land of opportunity? The geography of intergenerational mobility in the United States. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(4), 1553-1623.

Fisher, G. M. (1992). The development and history of the poverty thresholds. Social Security Bulletin, 55(4), 3-14.

Haskins, R. (2006). Work Over Welfare: The Inside Story of the 1996 Welfare Reform Law. Brookings Institution Press.

Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. (2024). The State of the Nation's Housing 2024. Harvard University.

Moretti, E. (2012). The New Geography of Jobs. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Newman, K. S. (1999). No Shame in My Game: The Working Poor in the Inner City. Knopf/Russell Sage Foundation.

Pearce, D. (2023). The Self-Sufficiency Standard for California 2023. Insight Center for Community Economic Development.