The Food Desert Myth: Zero Geographic Barriers, Clear Economic Disparities

When a county has excellent geographic access to grocery stores (0.57 miles average), yet SNAP participation varies 3.7× across neighborhoods, what drives food insecurity? Analysis of 408 census tracts reveals the barrier isn't distance: it's affordability.

Since 2019, grocery prices have risen by 25%, outpacing wage growth for the bottom quartile of earners.1 Today, a healthy diet costs nearly $1.50 more per day than an unhealthy one: a gap that adds up to $2,200 annually for a family of four.2

This statistical reality challenges what we thought we understood about food access. For decades, the leading explanation for poor diets in low-income communities was geographic: people lived too far from supermarkets. The "food desert" framework took hold around 2000, and it made intuitive sense. If we couldn't find fresh food nearby, how could we eat well?

That logic drove real policy. The federal government invested over $500 million into the Healthy Food Financing Initiative (HFFI) to build stores in underserved areas,33 and states created similar financing programs, including California’s FreshWorks Fund. The hypothesis was testable, the solution was concrete, and policymakers had a clear lever to pull.

But when researchers actually tested whether new supermarkets improved nutrition, what they found was more complicated. Opening stores in food deserts improved perceptions of access but barely moved the needle on diet quality or health outcomes.56 More detailed analysis revealed that 91% of the nutritional gap stems from demand-side factors (income, preferences, time), not geographic supply.

This wasn't a failure of the research; it was a refinement. We learned that geography was part of the story, but not the whole story. The real constraint turned out to be economic, not spatial.

Santa Clara County, the heart of Silicon Valley, is a good place to consider for this kind of policy work. The county is one of the nation's most affluent counties (median household income: $159,674),43 yet roughly 1 in 6 residents relies on food assistance from Second Harvest of Silicon Valley, a rate of need higher than the national average for food insecurity. If we look at this gap, a geographic explanation doesn't hold: there's no shortage of supermarkets. So what's actually driving it?

To find out, we can look at the 408 census tracts, combined 2023 SNAP administrative data, and verified 514 SNAP-accepting grocery stores. The results confirm that for urban and suburban communities, the "food desert" map is obsolete because the constraint has shifted.

The Landscape: Excellent Access, Deep Disparity

Santa Clara County is not a food desert. In fact, it is a food oasis.

Average distance to a SNAP-accepting store: 0.57 miles (an 11-minute walk).

Median distance: 0.41 miles.

Store Density: 514 verified locations accepting EBT, from large chains to local markets.

If geography were destiny, food security should be uniform across the county. Instead, we see a 3.7x vulnerability gap between neighborhoods.

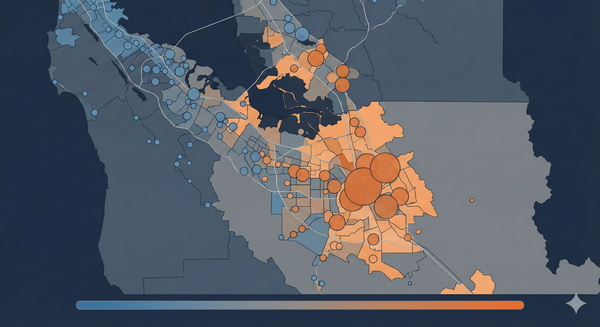

The East-West Divide

Using a vulnerability index that combines poverty, SNAP usage, and vehicle access, a stark map emerges:

High Vulnerability: East San Jose (Alum Rock/King & Story) and South County (Gilroy) show index scores of 0.45.

Low Vulnerability: Palo Alto, Los Altos, and Saratoga hover around 0.12.

In the highest-vulnerability tracts of East San Jose, the SNAP participation rate is 18.7% (nearly triple the county average). Yet, residents in these "hungry" neighborhoods live an average of just 0.51 miles from a grocery store, actually closer than the county average.

Figure 1: Data shows food insecurity clusters in East San Jose and South County, despite excellent grocery store coverage throughout the region.

The "Working Poor" Paradox

A key finding in the data is the profile of the highly vulnerable neighborhoods. These are not communities of unemployment; they are communities of the working poor.

Nationally, 56% of food-insecure households have at least one adult working full-time, a figure that has remained stable since 2017.10 In Santa Clara County, we see this play out block by block. We see tracts with:

- High employment rates

- High poverty rates

- Excellent grocery access (<0.5 miles)

- High reliance on food assistance

Translation: People are working full-time jobs, living within walking distance of a Safeway or Chavez Supermarket, and still cannot afford to shop there without government assistance.

The statistical correlation between "distance to store" and "SNAP participation" is actually weakly negative (r = -0.186).27 In other words, people in neighborhoods closer to stores are slightly more likely to need food stamps. This undermines the geography argument. If distance were the problem, the people farthest away would be the hungriest. They aren't. The poorest are.

Figure 2: The weak negative correlation confirms that distance is not the primary driver of food insecurity in Santa Clara County.

Why This Matters: Policy Is Lagging Behind Reality

Despite this overwhelming evidence, policy is slow to pivot. The "food desert" concept is intuitive and photogenic: a ribbon-cutting for a new grocery store looks like a win.

Federal: The HFFI continues to fund retail infrastructure through 2030.35

State: California recently passed SB 18 to fund the "Food Desert Elimination Grant Program."36

Local: Cities continue to offer zoning incentives for grocery retail in low-income areas.

These programs aren't bad; new stores bring jobs and dignity. But in an area like Santa Clara County, where the average resident is 0.57 miles from a store, building a closer store doesn't solve the problem.

If a family lives 0.3 miles from a grocery store but relies on SNAP to eat, the question isn't: "How do we bring the store closer?"

The question is: "Why can't this working family afford to shop at the store that's already there?"

This reframing changes the entire policy menu:

Housing is food policy: When rent eats 60% of a paycheck, the food budget is the first thing to be cut.

Wages are food policy: A minimum wage of $17.20 doesn't cover the cost of living in a county where median rent is $3,200.

Benefits are food policy: We need to shift from supply-side interventions (bricks and mortar) to demand-side interventions (SNAP expansion, fruit & vegetable incentives, and cash aid).

Caveats: When Geography Still Matters

It is important not to over-correct. "Food deserts" are a real phenomenon in:

- Rural America: Where the nearest store is 10+ miles away.

- Transportation-poor pockets: The ~0.6% of the U.S. population without a vehicle who live >1 mile from a store.28

- Isolated Communities: Indigenous reservations or towns without potable water access.

But for the vast majority of urban and suburban America (and specifically for Santa Clara County), geography is a solved problem.

Conclusion: From "Food Deserts" to "Economic Deserts"

We need to retire the term "food desert" for urban environments. It implies a natural phenomenon, a lack of rain. What we are seeing is an "economic desert": insufficient purchasing power.

Santa Clara County proves that you can have perfect physical infrastructure and still have massive hunger. As we move forward, our research priorities must shift from measuring miles to measuring the cost of living, the adequacy of safety nets, and the economic constraints facing working families.

Methodology Note

This analysis updates prior research by the Food Empowerment Project (2010) and UC Davis (2021) with new 2023 administrative data. It utilizes:

Unit of Analysis: 408 Census Tracts (approx 4,000 people each).

Data Sources: Census ACS 5-Year Estimates (2019-2023), California Department of Social Services SNAP Data (2023).

Store Verification: A three-tier verification process (USDA database + Chain verification + Manual sampling) confirmed 514 SNAP-accepting locations, filtering out liquor stores and non-food retail.

Income Definitions: Note that while Census Median Household Income is $159,674, HUD's "Area Median Income" (AMI) for housing eligibility is higher ($184k-$195k), reflecting the extreme local cost of living.

Full data tables and Python code are available upon request.

Let's Discuss:

The Map vs. The Reality: Does your neighborhood feel like a "food oasis" (plenty of stores) but an "economic desert" (nobody can afford them)?

The Fix: If we stop focusing on geography, we can think about the underlying economics. What's the single biggest change that would help families in your area: Lower rent? Higher wages? Or better food benefits?

References

[1] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index (Food at Home), 2019-2024. ↩

[2] Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (Mozaffarian et al.), "The cost of healthy vs. unhealthy diets," BMJ Open, 2013 (adjusted for inflation). ↩

[5] Allcott, H., et al. (2019). "Food Deserts and the Causes of Nutritional Inequality." The Quarterly Journal of Economics. ↩

[6] Elbel, B., et al. (2015). "Diet And Perceptions Change With Supermarket Introduction In A Food Desert, But Not Because Of Supermarket Use." Health Affairs. ↩

[10] USDA Economic Research Service (2024). Chart of Note: Employment and Food Insecurity. ↩

[27] Author's calculation: Correlation (r) between tract centroid distance to nearest SNAP retailer and SNAP participation rate. ↩

[28] Allcott et al. (2019). ↩

[33] NIH Workshop on Food Insecurity and Health (2024). AJPM Focus. ↩

[35] Reinvestment Fund (2025). HFFI FARE Fund Awards. ↩

[36] California Legislature, SB 18 (2025). ↩

[43] U.S. Census Bureau, ACS 5-Year Estimates (2023). ↩

Tags: #FoodSecurity #FoodDeserts #DataAnalysis #PublicPolicy #SantaClaraCounty #Economics #SNAP